In a world where children are introduced to the world of “bees” through stories of a single species – the introduced Apis mellifera (European honeybee), it was extremely refreshing to find a children’s book that included a variety of Australian indigenous bee taxa.

Review by Kit Prendergast

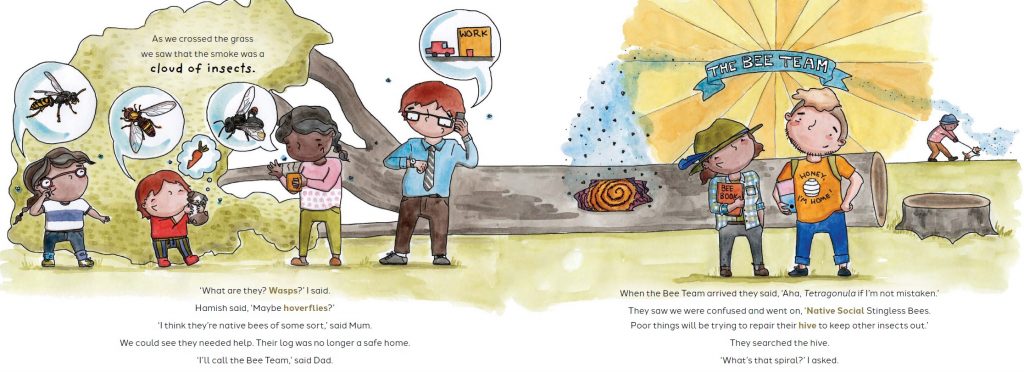

Bee Detectives by Vanessa Ryan-Rendall & Brenna Quinlan is a charming book, aimed at primary school-age children, describing how the event of a tree being cut down causing Tetragonula carbonaria to be disturbed alerted a brother and sister (Hamish & Olivia) to investigate the world of Australian native bees.

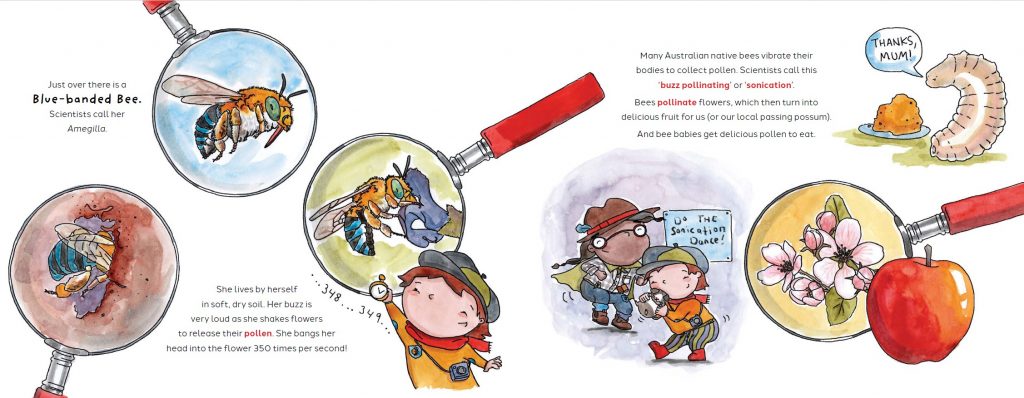

The best aspect of this book was the illustrations – in particular, of the bees! Illustrators often take “artistic licence” when it comes to illustrating bees; I personally dislike this tact, especially for children’s books which should be subtly introducing and educating children whilst entertaining. But I found no two-winged “bees”, or bees with just one or two body segments, or with big smiley faces – instead I found an absolutely beautiful set of illustrations where the illustrator clearly made detailed observations of photo-graphs of the taxa so that they could be true to reality, whilst also having the artistic flair. The more stylised ‘cartoon’-like characters were the humans, and I loved the little guinea pig side-kick. It was also nice to see a diversity of ethnicities represented and both a male and female made up the ‘Bee Team’ as well as the ‘Bee Detective’ team.

For the most part, I was also thrilled that the author did not “dumb it down”- the prose could easily be understood by children and they introduced terms like “entomologist” and “sonication.” It was therefore somewhat disap-pointing that they still adhered to the common names (e.g. “blue banded bee” – despite numerous Amegilla species lacking blue bands, and unrelated taxa such as some Nomia having blue bands; “Resin bee” (depicted by Megachile deanii) which suggests a single species rather than collectively referring to many, but not all, Megachile, and overlooks how many other bees collect resin, including the Meliponini). Similarly, it seems unnecessary to make up common names which include genus names (but of the host genus in the second instance) and then not provide the correct name of the “Feathery Leioproctus Bee” (Leioproctus plumosus) and “Persoonia Bee” (unclear which species this is, as a number of bees in the subgenera Leioproctus (Cladocerapis) and Leioproctus (Filiglossa) forage on Persoonia, but presumably Leioproctus (Cladocerapis) carinatifrons)).

As someone who has worked with children’s education for over a decade, I have always observed children have no diffi-culty in learning the correct sci-entific names (as anyone can see from the aptitude of chil-dren rattling off dinosaur names like Brontosaurus, Stegosaurus, Tyrannasaurus rex). Reinforcing this disconnect between a glob-al language for species vs. that of the public is how the author suggests “only scientists” call “blue banded bees” Amegilla or one of the “social stingless bees” Tetragonula carbonaria.

Nevertheless, I do appreciate the author’s occasional inclusion of scientific names, especially in a time when taxonomists and taxonomy are needed more than ever, but are tragically underappreciated. It would also have been nice to see Euryglossinae represented, given that they are endemic to Australia and the most species-rich of the subfamilies.

Overall the educational content was excellent, however there were a few errors: Megachile (Eutricharaea) fe-males, when they cut leaf discs to line their nests do not make jagged zig-zag lines, but instead leave almost perfect circular discs. Rather than social bees being only repre-sented by Meliponini, other social bees include Allodapini, and many of the halictids. Amegilla will often live in hard soil, not just “soft soil.” The image of the Amegilla in which the child characters are counting how many times she ‘bangs’ her head to sonicate it is actually a bee collecting nectar from a flower that does not require sonication. Saying that “there are so many types of stingless bees” is not really accurate given the 11 described species represent less than 1% of the estimated 2,000 species of Australian native bees. It is also inaccurate that ‘all species of sting-less bees are very useful for producing food such as …tomatoes’ (these require sonication and the Australian Meliponini are not buzz pollinators). I also found some of the definitions in the glossary somewhat lacking e.g. “pollen: fine yellow grains produced by flowering plants.”

Whilst I am eager to see native bees represented, it is a pity that native bee scientists do not appear to be consult-ed during much public outreach material which would prevent such errors from being published, especially in educa-tional material.

In a world where children’s books on bees are over-represented by the introduce European honeybee Apis mellifera, this book is a much-needed and welcome addition, and furthermore, represents a greater diversity of Australian native bees than any of the few children’s books published to date, which also focus on the “sugarbag” bees. The illustrations were delightful, as well as the narrative, and I am glad that there is an increasing representation of native bees and their ecologies in children’s literature.

Review by Kit Prendergast

Hardback, $25, buy here: https://www.publish.csiro.au/book/7962/